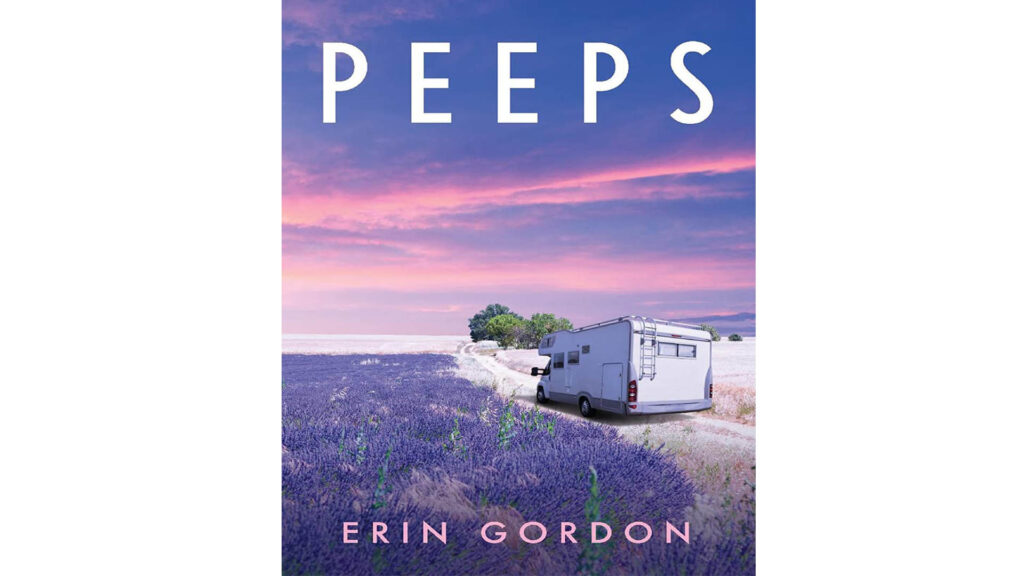

A coming-of-middle-age novel that takes to the road.

QUITE FRANKLY, at age 51, Meg’s life is not what she expected. Living in the aftermath of an unforeseen divorce, her life is buffeted by fear, family history, and her therapist’s advice. That is, till she decides to do something rash and buy an RV. Leaving the comforts of Santa Monica behind, she takes her fledgling podcast, Peeps, on the road. Meg doesn’t have too much trouble whittling down her belongings. She does, however, carry the weight of her past. Her mother’s cruelty. Her recent divorce. Her suspicions about genetic determinism.

Taking a route that zigzags like an EKG, Meg drives her RV across the continent toward fresh waterfronts, new interviews, and distant relations—a journey that she hopes will help reconcile her past and possibly redirect her future. So Peeps begins. And, as every good novel is about ideas, so Erin Gordon’s fourth and latest work of fiction explores the concept of the Big Life. What is it? And how do you live it? Those questions propel Meg forward and park at the center of her podcasts.

The novel itself alternates between travel narrative and transcripts of Meg’s interviews—where she asks every guest seven illuminating questions. That artful balance gives Peeps the defining characteristics of life on the road: movement and conversation. Like the podcast itself, the novel progresses quickly and naturally, covering a range of emotions—mirroring the strange fluidity with which life moves from the comic to the tragic and back. But, like Meg says about her podcast, “that’s the premise of Peeps: that everyone’s life—even the smallest, most insular life—is a story worth hearing.” Now, truth be told, we don’t love every stop on Meg’s journey.

There are a few places where the narrative stumbles into stereotype. The most noteworthy example is during Meg’s first stop at a dump station near Lake Tahoe. There, Meg is approached by two flannel-wearing hunter types in a rusty van. They reek of beer and tobacco, wear massive knives in their belts, and leer at her expectantly. Asking if she wants to “hang,” one of them claws his hand inside her window, before she manages to escape to Wal-Mart nearly traumatized.

In fact, for the rest of the novel, Meg successfully keeps her fellow campers at arm’s length—an inescapable contrast with the genuine human curiosity she shows to strangers during her podcast interviews. But Peeps is a journey of growth. At the beginning of the novel, Meg is a newbie. By the end, she is not the same. She can handle herself and opens up to the campground crowd. Because, true to life, the revolving string of victories and defeats change us. Newbies toughen up. Get wiser. And move ever closer to the Big Life. And that, ultimately, is what makes Peeps worth reading.